Geopolitical impact of the Coronavirus on the Global Order, the EU and the MENA Region

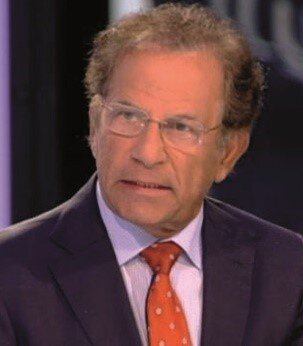

Professor Bichara KHADER

bichara.khader@uclouvain.be

Dr Bichara KHADER est belge d’origine palestinienne. Il est professeur émérite de l’Université Catholique de Louvain et fondateur du Centre d’Etudes et de Recherches sur le Monde Arabe Contemporain. Il a été membre du Groupe des Hauts Experts sur la Politique Etrangère et de Sécurité Commune (Commission Européenne) et Membre du Groupe des Sages pour le Dialogue Culturel en Méditerranée (Présidence Européenne).Aujourd’hui , il est professeur visiteur dans différentes universités arabes et européennes. Il a publié 30 ouvrages dont les derniers sont :

1.Le Monde Arabe expliqué à l’Europe (français et espagnol)

2.L’Europe pour la Méditerranée (français, espagnol et arabe)

3 Europe and the Arab World: an assessment of EU policies (arabe, espagnol et anglais)

Dr Bichara KHADER is Belgian pf Palestinian origin. Heis Professor Emeritus at the Catholic University of Louvain and Founder of the Study and Research Centre on the Contemporary Arab World. He has been member of the Group of High Experts on European Foreign Policy and Common Security (European Commission) and Member of the Group of Wisemen on cultural dialogue in the Mediterranean (European Presidency). Currently he isvisiting professor in various Arab and European universities. He published some 30 books and hundreds of articles on the Arab World, the Euro-Arab, Euro-Mediterranean and the Euro-Palestinian relations. The most recent books are:

1.Le Monde Arabe expliqué à l’Europe (French and Spanish)

2. l’Europe pour la Méditerranée (French, Arabic and Spanish)

3 Europe and the Arab World: an assessment of EU policies (English, Arabic, Spanish)

Contents

PART I:

US-China tit-for-tat game

1.US leadership is declining

2.China is not going to fill the power vacuum

PART II

The EU revealed

1. The EU caught off-guard by the virus

2. Charting a new course of action

PART III

The Pandemic stripped bare the MENA REGION

1.The pandemic struck at the worst moment

2.The economic cost of Coronavirus for the Arab economies

3.No change in regional dynamics

PART IV

The EU and MENA Countries in times of Coronavirus

1.Immediate challenges in the midst of the pandemic

2.EU Mediterranean and Arab policy after the pandemic

3.Regionalised Interdependence

Introduction

Coronavirus epidemic will be reported in history books as the most world-shattering health disease, since the “Spanish flu” one century ago. As of this writing, 15th of May 2020, the disease has exacted a human toll, exceeding 200.000. More than half of the world population has been locked-down. In almost 195 countries, measures ranging from partial or total confinement to curfews have been taken and enforced, causing economic devastation and financial havoc.

Everywhere, lives have been disrupted. Images of empty streets in Paris as well as in Amman or Algiers will remain in the memories for generations to come. Seeing the Pope celebrating Easter in an empty St Peters Cathedral, in Rome, captures the scale of this defining moment.

The far-ranging consequences of this epidemic will not be limited to an economic recession, probably never seen since 1929. It will also have a transformational effect on States and societies and will certainly lead to significant shifts in the distribution of power at the international level.

It appears that the virus has probably broken out, in December 2019, in the industrialised Chinese region of Wuhan. After its initial missteps and underreporting of the number of deaths, China seems to have contained the epidemic. But the virus migrated to Europe where, in the initial phase, Italy and Spain became the new hotspots before its spread to almost all European countries. But the countries reacted differently to contain the virus: some countries imposed a two months lockdown, shuttered nurseries, schools and universities, closed borders, banned travel, grounded planes, but Holland and Sweden opted for what was called “Herd immunity” with little success. In all countries supply-chains have been disrupted causing severe economic recession. But the epidemic has caused another severe damage related to the future of the European Project itself.

The US has not been spared either. And although President Trump ,in his first declarations, tried to downplay the threat ,saying that it is under control, and that democrats are using it as a “new hoax”[1] to get rid of him, he had to acknowledge later the magnitude of the disease as the US has overtaken China and Europe in the numbers of infected and dead. The epidemic will probably recede or disappear but its geopolitical consequences on the standing and the reputation of the US will be severely felt.

Arab, Mediterranean and other Mena countries have also been struggling with the virus. Iran and Turkey have been severely hit. Egypt confined partially its population but locked-down information about the pandemic. Gulf countries and their expatriate workforce have also been affected. War- stricken countries like Syria, Yemen, Libya suffered most because of their precarious health infrastructure and the on-going conflicts. The Palestinian territories in the West Bank had few hundred cases, but the risk of exponential spread of the pandemic is higher in Gaza Strip which lives under Israeli siege, since 2007, and is overpopulated, with little living space, and precarious medical facilities and equipment. Iraq and Lebanon were not spared at a time of political instability and street protests. North African countries have also been hit. Israel has not been an exception with thousands of infected and hundreds of dead, mainly in the Haredim Communities and even in the army.

For now, 195 countries are still grappling with the disease, in the hope that research centres will soon find a drug or a vaccine that will allow them to go back to normalcy. This may take months, if not years. In the meantime, the transformational geopolitical effects of Coronavirus will be significant and probably wide-ranging. Josep Borrell, the EU High Representative aptly described the challenge to come:” Covid-19 will reshape our world, we don’t know when the crisis will end but we can be sure that the time it does, our world will look different”[2].

This paper seeks to shed some light on the possible geopolitical consequences of Coronavirus at the international level, mainly regarding the US-China rivalry, on the EU future and on its relations with its “Mediterranean and Arab neighbours, and on the MENA region, as a whole. The research questions are the following: will this global health disease exacerbate US-China competition or will it usher in more cooperation? Will it put the EU project at risk or will the EU transform this crisis into a new opportunity for a stronger and safer Europe? Will this crisis lead to another AMENA’s (Arab Middle East and North Africa) future freer, more integrated, more prosperous or to the consolidation of the current stalemate or even to failed states? And, finally, will this crisis reinforce the current apathy in the EU-Arab relations or will it force the EU to assess critically and rethink its relations with its neighbours, overhaul its old-fashioned policies, and inject new life in its global outreach?

PART 1.

US-China: tit-for-tat game

US-Chinese relations have never been cordial. But since the election of President Trump, they became even more tense and rocky. Trump accused China of dumping, unfair competition, currency manipulation, excessive trade surpluses. And geopolitically, there is a common belief in the US administration that China is engaging in a systematic endeavour to counter the US hegemony, in reference to the supposed China-Russia-Iran axis, to regional Chinese initiatives such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation or to the 2013 Road and Belt Initiative.

President Trump resorted to a policy of “maximum pressure” to force the Chinese to negotiate a new trade agreement which would help increasing American exports to China and thus reducing the trade deficit. And indeed, an interim agreement has been inked, to that effect, on January 15,2020. Reluctantly, China had to show flexibility as almost 20 % of its GDP derives from exports and the US is its largest export market. Yet, in spite of this partial agreement US-Chinese relations remained inimical and sour.

One might have expected the Coronavirus epidemic to be an opportunity to bury the hatchet of discord and to bring the US and China closer, as the fight against the virus requires international cooperation. The opportunity has been missed as President Trump engaged in a blame game, hurling insults at China, calling Coronavirus a “Chinese virus”, and even asking China to shoulder its responsibility in its spread. In early April 2020, President Trump went even further in his hunt for scapegoats, accusing the World Health Organisation of being “China-centric”, and suspending America’s financial contribution to the Organisation in the midst of the global health crisis. Some American analysts followed suit and claimed that the virus originated from “Chinese covert biological weapons’ program”.

In response to this “war of words”, a spokesman of the Chinese Foreign Ministry, Zhao Lijiang, retorted that the virus was a US-created “bioweapon” , probably brought to China by American soldiers who took part in the 7th military games of Wuhan, in fall 2019, with the objective of weakening the assertive position of China in the global arena. Although China later backed away and adopted a more conciliatory tone, the “bioweapon theory” has flourished in many parts of the world.

1.US leadership is declining

Thus, the virus evolved into a tit-for-tat war of words. It encapsulates the crisis of multilateralism but mainly the “glaring loss of US leadership”[3],illustrated by the initial trivialisation of the epidemic in the US, the mishandling of its outbreak, the overwhelming of American hospitals and the shortages of medical supplies such as masks, gowns, ventilators and respirators. The press coverage of Chinese planeloads of medical supplies to Italy, Serbia, Algeria, Egypt and other countries showcase how America is “off the map” and how it lost the war of narratives.

We can multiply the examples of US loss of political and moral leadership, such as banning the travel to the US of EU citizens without previous coordination with EU officials, or the intensification of sanctions on Iran, another hotspot of the Coronavirus and in dire need of medical supplies or the tightening of the screws on Venezuela ,offering even 15 million dollars to capture President Maduro .

All these measures, and many others, are inflicting severe damage to America’s standing and reputation. Already in many countries, mainly in MENA region-which includes the Arab countries, Turkey, Israel and Iran- the so-called US “benevolent hegemony” was in shambles. Since taking office in 2017, Trump has undermined multilateral alliances, focused on great-power competition, resorted to” maximum pressure” policies, failed his European allies, lashed at NATO, and proved to many MENA countries to be an “unreliable ally”. With the exception of some Gulf States where the US is “subcontracted” as security provider, or Israel where President Trump is cherished for his “deal of the Century», in all other MENA countries, faith in the US has plummeted. The US was clearly on a slippery course as World leader before the coronavirus. However, no doubt that the Coronavirus epidemic will accentuate and accelerate the process, as the US “has showed itself to be anything but a model”.

It is probably too soon to indulge in prospective analysis and see whether the loss of US standing and reputation will have temporary or lasting effects, in terms of “de-Americanisation” of the world order, and the end of American hegemony. There is no consensus on this issue among American political analysts. In the debate organized by “Foreign Policy”, in March 2020, on the geopolitical impact of the epidemic, Kori Schake argues that the US has “failed the leadership test” and that it will “no longer be seen as an international leader”. For Robin Niblett, “the Coronavirus pandemic could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back of economic globalisation”. Kishore Mahbubani believes that the pandemic will accelerate “a mov -away from a US-centric globalisation to a more China-centric globalisation”, while Shivashankar Menon thinks that” the pandemic will not be the end of an interconnected world” as the pandemic, itself, is the proof of such independence. On his part, John Allen remarks that the history of Covid-19 will be written by the victors and that the crisis “will reshuffle the international power structure” … resulting “in widespread conflict within and across countries”. Joseph S.Nye, Jr. believes that American strategy focusing on great -power competition has been inadequate and that” it is not enough to think of American power over other nations”, and “that the key to success is learning the importance of power with others”, adding that “ Covid-19 shows we are failing to adjust our strategy to this new world”.

In April’s 2020 issue of the Journal of “Foreign Affairs”[4], Richard Haas offers an articulate analysis of the geopolitical impact of the pandemic. For him,” the world following the pandemic is unlikely to be radically different from the one that preceded it”. It is true that in “the world that follows this crisis will be one in which the US dominates less and less”, but the trend of the precipitous decline in the appeal of the American model was already “apparent for at least one decade”, as a “result of American faltering will rather than declining American capacity”. The appeal of Trump’s “America first” just accelerated the trend as this slogan was based on the” assumption that much of what the US did in the world was wasteful, unnecessary and unconnected to domestic well-being”, and that the US must “ devote resources to needs at home” rather than squandering them abroad. The pandemic will just be another incentive for the US to renounce on “taking on a leading international role”.

2.China is not going to fill the power vacuum

The fact that the US is losing leadership, does not mean that China has won , that it can capitalise on the void left by the US and that it has the desire, the will, the ability and the resources to become a credible alternative to the US, as a global leader.

It is true that China turned its success in the handling of the health crisis into a “larger narrative of competence, efficiency and domestic governance”,[5] in comparison of what was dubbed in Chinese media as “American irresponsibility” and “incompetence”.

It is also true that China has cleverly engaged in a massive “soft power campaign”, extending a helping hand to dozens of countries, sending medical supplies and even medical personnel. But it was not mere charity. In fact, Chinese leadership pursued two objectives:

First, to show to its domestic audiences “images of grateful Europeans[6], Arabs, or Africans, and even images of presidents, like the Serbian president, kissing the Chinese flag and praising China’s solidarity[7]. By acting so, China seeks, indirectly, to silence its domestic critics, dissidents and Hong Kong’s protesters. Let us remember that in its initial response to the coronavirus, China silenced the doctors who warned of the emergence of the new virus.

Second, China is keen to demonstrate to the world at large it’s moral superiority”, as a “compassionate country”, by launching its self-promotion offensive.

Whether Chinese “charm offensive” will succeed in silencing dissidents and protesters, at home, is difficult to assess. As for its impact abroad, no doubt that some media, parties , and even leaders, mainly in authoritarian Arab [8]and African countries, embraced the Chinese narrative and applauded its methods in combating the outbreak and the celerity with which it sent medical supplies. In the West, by contrast, we saw mixed reactions of gratitude, from many European leaders, and vilification, mainly in the US in particular, where Chinese public relations’ campaign was discarded as “propaganda”[9], “window-dressing”, “face-washing”, and even “bad Samaritan”.

Undoubtedly, providing assistance to foreign countries was not a mere act of compassion but a “geopolitical goal”. Javi Lopez put it bluntly:” This is not altruism: it is a demonstration of China’s will to play the role of ascending hegemon” [10].

But will China be «an ascending hegemon”, overtaking the US, in terms of clout, influence, leverage and leadership?

While it is an undeniable fact that China has become a great power and an important powerhouse, it is nevertheless unrealistic to believe that Coronavirus is a “divine benediction” which will allow China to fill the power vacuum and become an alternative hegemon. Outsmarting the US and the West in general in the handling of the pandemic is not a sufficient condition of global leadership. In other words: the successful response to Covid-19 does not make China a recognized, respected, and accepted World Leader, because China suffers of many contingent handicaps and stifling structural vulnerabilities.

The Coronavirus hit China at a time when its economy was already slowing and US-China trade war was going on. Coronavirus will accelerate the economic downturn as it will severely affect trade, access to raw materials and supply chains. Moreover, China does not have a currency that can compete with the hegemony of the dollar and it is too dependent on foreign energy flows and on external demand, mainly from the US, the EU and Asian and Arab countries. Ultimately, the pandemic is set to have disruptive effects on Chinese economy.

But China will face another challenge: Indeed, there are voices in the West calling for “de-coupling” and “relocation of strategic production”, like medical protective equipment and medicines, for reasons related to peoples’ anxieties about health security. This does not augur well for Chinese economy.

More importantly, Chinese foreign policy is mainly trade-driven and China has been loath to engage in security issues by choice and convenience. First because China does not want to overstretch its military resources and increase its global outreach. And, second, because China dislikes the idea of meddling in the internal affairs of foreign countries or finding itself embroiled in regional conflicts. As a matter of fact, while the US dispose of dozens of military bases across the globe, China has only one military facility in Djibouti. Thus, by abstaining to play a global leading security role, China may avoid squandering resources on unnecessary wars (such as the American invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq) but, at the same time, it diminishes its attractivity as “security guarantor” or as responsible contributor to world peace.

Yet, China has the historic depth, the size, the demography, the talent, the technology, and time on its side. But is the Chinese authoritarian model sufficiently attractive to garner support, credibility, influence, adherence, and respect, qualities indispensable for a leading global power? Yes, would say other authoritarian regimes, but surely not, would say the peoples aspiring to freedom and democracy. To put it in a nutshell, there will be hardly a ‘Chinese dream”, after the vanishing of the American dream. But there will be a pivot to the East (ASIA) as the new centre of gravity of power, innovation and growth.

Summing up

There is a consensus among political analysts that America’s power, at least since the end of the bi-polar rivalry, three decades ago, has been misused and has done more harm than good to multilateralism, to transatlantic relations and to world peace and security. The pandemic brought another proof that the US “has failed the test of leadership”, but this does not mean that the seismic shock of this global health crisis will significantly and permanently change the international system to the advantage of China. China will not take up the role of the US as it suffers from structural vulnerabilities: possible disruptions of supply chains and trade relations, weak security provision, scarcity of raw materials, unattractive political model, and reluctance to assume the responsibilities attached to a Great Power’s role. Therefore, it is unrealistic to believe that it will become an alternative model and an “indispensable global actor”. What it is possible, however, is the reinforcement of current trends of a multilateral world “where power is dispersed” among Regions, and States, but with a clear pivot to “Asia

PART II

The EU revealed

1.The EU countries caught off-guard by the virus[11].

In few weeks, Italy, Spain, and France surpassed China in numbers of infected and dead. Other European countries followed the same trend. With the exception of Netherlands and Sweden, two member states that opted for “herd immunity”, almost all other EU countries quarantined their population, halted non-essential business, sealed off their external borders, shuttered their schools and universities, closed their airports and grounded their fleet.

The exponential spread of the epidemic overwhelmed hospitals[cs1] , disrupted health systems, exposed health personnel to infection. In almost all countries, the lack of masks, gowns, respirators and ventilators and diagnostic test kits has been alarming.

Converging economic forecasts predict economic slump and even recession, with double-digit deficits, skyrocketing unemployment, and increased public debt, putting at risk social cohesion and political stability.

With a crisis of such magnitude, one might have expected a common, coordinated response and a renewed solidarity. Unfortunately, when the pandemic struck,” Nation States stepped in not the EU “[12]. There has been a “battle of masks”, uncoordinated restrictions on free-trade and border closures. Italy, in particular, regretted that other fellow states did not hurry up to send masks, ventilators or respirators while the country became the first European hotspot of the pandemic.

The EU has been unfairly accused of failing the stress test of Coronavirus, but a key lever, such as Health, still remains in Nation-States’ hands[13]. And as the Arab proverb says: a jockey cannot run faster than his horse, which means that the EU action remains always constrained by its Member States’ choices and policies.

But the pandemic has laid bare another EU’s vulnerability: the lack of collective solidarity, prompting political analysts to argue that Coronavirus “exposed the truth about the EU: it is not a real union”[14]. Jacques Delors, former President of the EU Commission, regretted this lack of solidarity and warned that “it put at great risk the future of the EU[15]” as collective solidarity “is the founding pillar of the EU”. Enrico Letta, former Italian Prime Minister, spoke of a “deadly risk” for the EU.

This lack of solidarity became appalling when the Eurogroup discussed the financial rescue and recovery packages. It is true that the EU did not remain idle: a” temporary emergency purchase programme” has been adopted, as well as a SURE plan for those who lost their jobs and ,on April 23, the EU agreed on the impressive sum of 540 billion euros relief deal, in the form of credit-lines, via the European Stability Mechanism, for countries hit hardest by the pandemic, “without conditions attached[16]”. But 9 Southern European countries wanted the EU to go further. Pedro Sanchez pleaded for a “Marshall Plan” and a new Debt mutualisation mechanism”, in the form of Eurobonds to ensure the Continent’s economic recovery[17]. Mario Draghi, former ECB President, followed suit.

The proposal of debt-sharing was rejected by Netherlands, Germany, Austria and other Northern European countries, on the pretext that debt-sharing is banned by the treaties that created the Eurozone, and that it will discourage Southern European countries from undertaking painful reform. They have a point, explains Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform, but the alternative – “eurozone members sinking into a negative spiral of falling GDP and rising debt, and perhaps exiting the EU- would be worse for all concerned”[18]. Yanis Varoufakis, former Greek minister of Economy, is on the same line. For him, without Eurobonds “the eurozone will remain an iron cage of austerity for most and a source of economic stagnation for everyone”[19]. Mario Centena, the President of the Eurogroup, sounded the same alarm:” This is not a time for business-as -usual policy”, he said to the Eurogroup meeting on April 7. Even in countries opposed to “Eurobonds”, there have been voices, like the German Secretary of State for European Affairs, Michael Roth, who called for increased solidarity with Italy and Spain as Germany, an exporting country, “may suffer from the collapse of these two countries”[20].The German Chancellor, herself, recognized that «Germany will not be strong in a weak Europe”[21].

As of this writing (May 15), the question of Eurobonds has not yet been settled, with the Dutch government sticking to its opposition to plans for big spending. “Covid-19 poured cold water on Netherlands’ EU romance”, observed Jennifer Rankin[22]. Unfortunately, the Dutch are not alone, but they looked tougher, for fear that sharing debt would fuel populism in the North of Europe. The argument is not baseless. But, refusing mutualised debt may fuel populism in the South. As a matter of fact, a poll conducted in Italy, on 12-13 March 2020, found that 88% of Italians felt that the EU was failing its support to Italy. Thus, the EU is caught between a rock and a hard place. A lack of solidarity could be the final straw for the EU project, as Southern populist forces will exploit perceived EU shortcomings, the uncoordinated response to the pandemic and the popular anxieties to “campaign against EU mainstream parties and policies”[23]. But if there is an increased solidarity, then populist forces in Central and Northern Europe will fan claims about “an EU, incompetent and wasteful bureaucracy”.

The 4th EU summit, on April 23,2020, authorized the Commission to flesh out a huge recovery package but positions remained divisive over debt and grants, and no consensus has been reached on Eurobonds or on the Spanish proposal of 1.5. trillion Recovery Fund through “perpetual EU debt”.

With no consensus in sight, the risks for the future of the EU are real. When the pandemic recedes, the EU will be at great pain regaining the confidence of its citizens and restoring faith in its future. Yet the EU is not doomed to failure. Ultimately, this pandemic may serve as a wake-up call for a better, stronger and safer Europe.

The EU can, and must, transform this crisis into an opportunity. It is a question of will and choice. Leila Slimani reminds us that Greek term for “crisis” is “Crineo”[24], which means “to choose”. Therefore, much will depend on the path that EU will choose to take

2. Charting New Course of Action

1) The EU cannot, for its health safety and security, over-rely on one single export market: the Chinese market. Such over- reliance exposes the EU to blackmail and disruption.

2) The EU should spur investors to relocate strategic public goods and medical equipment. However, the EU should not cede to the temptation of “de-coupling” from China, but bring home essential industries. The EU Commission has already mentioned “the protection of critical European medical assets”.

3). The EU is the biggest trading partner of China and China is now EU’s second biggest trading partner after the US. Maintaining good relations with China is strategically relevant. In its joint communication to the EU Parliament and the EU Council, intitled “Elements for a new strategy on China”(2016), the Commission describes China as being simultaneously “a cooperative partner”, a “negotiating partner”, an “economic competitor” and “a systemic rival” promoting alternative models of governance[25]. Yet the Communication insists that the EU should continue to engage China, deepen its multidimensional relations with this rising power, but, at the same time, robustly seek more balanced and reciprocal conditions governing the economic relations, to ensure a level-playing field and the upholding of a rules-based multilateral trade. Win-win partnership, reciprocity and transparency should therefore be the cornerstones of a renewed EU-China cooperation. Nevertheless, for its own sake, the EU should not adopt hawkish positions, engage in trade wars, or get involved in the US-China rivalry, as its ripple effects will hurt European interests.

4) The EU has gone too far in dismantling strategic public sectors, mainly health sector, with excessive trust in the private sector. This led to the current crisis[26]. This does not mean that the liberal model has failed, but that the retreat of the State, from strategic sectors, has been an error.

5.Diseases, like Covid-19 will occur in the future. Therefore, the EU should heavily invest in medical research and in its health systems, avoiding unnecessary duplication. It cannot afford, another time, to be caught unprepared.

6. As the pandemic has been a stress test for the credibility of the EU, the primary goal should be the protection of its citizens. Consequently, the social dimension of its emergency and recovery stimulus mechanisms should occupy centre stage.

7. The principle of collective solidarity should be upheld as a “founding pillar” of the European project. If the EU cannot adequately respond to its 450 million citizens’ needs, then, “national governments might take back more powers from Brussels”[27]. Pedro Sanchez, the Spanish Prime minister, summed up the challenge facing the EU:” Without solidarity, there is no cohesion, without cohesion there will disaffection and the credibility of the EU project will be severely damaged”[28].

8. At no moment, the EU should accept the erosion of the democratic standards or the exploitation of the emergency laws by certain governments to tighten their grip on power.

9. The UE should expose the futility, the inanity and the vacuity of the far-right narrative that endangers social cohesion and political stability, by forging a counter-narrative of consistency, coherence, cooperation, solidarity and unity of purpose. It should not let far-right networks win “ the war of narratives” and exploit the pandemic to disseminate disinformation [29]such as “ migrants spread the virus”, or “ nations with tightly-controlled borders have coped better with the pandemic” , or that “ authoritarian regimes are better equipped to outperform liberal democracies in tackling the health crisis “ , or even that “the liberal order is on the verge of collapse”. It does not suffice to demonstrate the ineptitude and non-sense of such “narrative», as today’s global challenges ( such as pandemic or climate change) cannot be addressed merely at national level and that only a multilateral rules-based cooperative governance is the most rational course of action.

9. The live-shattering economic recession, as a result of the pandemic, will force governments to dedicate their resources to rebuild at home.There may be areduced incentive to tackle other pressing regional or global problems such as climate change, or to increase assistance to its Southern Arab, Mediterranean, and, even African neighbours. Although the EU has been hard hit by the pandemic, it cannot, for reason of security and humanity, leave its Arab, Mediterranean and African partners to their own fate.

There are birds of ill-omen for whom the EU is an exercise in fantasy or a wasteful “bureaucracy”. They are wrong as they miss a point: the EU is not simply a single market but a collective peace project. As such, it will survive the stress test of the pandemic. Because the alternative is simply cataclysmic with creeping far-right populism and authoritarianism and ultimately grim prospects of new battlefields.

Summing up

EU countries have been badly hit by Coronavirus. Italy and Spain became the new epicentres of the pandemic, in Europe. Both EU countries have been stunned and disappointed by the lack of solidarity from other fellow members, in contrast with Chinese “self-promotion offensive”. The initial missteps of EU countries have triggered widespread criticism.

The internal “war of masks” among EU countries was compounded with another more substantial issue related to the economic stimulus packages as the proposals of “Eurobonds” or the “ eternal debt” have been met with suspicion.

Covid-19 revealed that States’ healthcare systems are badly equipped and under-financed to deal efficiently with such a life-shattering health crisis. It revealed also the appalling lack of solidarity among EU member states, putting EU cohesion at risk. Yet, the EU can transform this crisis into an opportunity if it charts another course of action reaffirming the centrality of collective solidarity, the relocation of strategic production in Europe and in its immediate neighbourhood, and finally the necessity for a “more geopolitical Europe”.

PART III:

The Pandemic stripped bare the MENA REGION

1. The pandemic struck at the worst moment

Like all countries of the world, MENA countries (Middle East and North Africa) are feeling the sting of the pandemic[30]. Al-Jazeera TV documents the total number of infected and dead but, in some countries, underreporting is prevalent. All countries established quarantines and even curfews. Prayers in Mosques (even in the holiest cities of Mecca and Medina) and Churches (even in the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem) have been banned, triggering some protests from Imams and clergymen.

Before the outbreak of the epidemic, MENA countries had no shortages of crises. Plagued with bad governance and state incompetence, all countries delayed their response to the disease, allowing the spread of the virus. Such delay posed daunting challenges as Health Systems are poor with hospitals lacking essential medical equipment. Over-crowded camps of refugees and displaced Syrians (in Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and Iraq), Population density (mainly in Gaza and Egypt), increased mobility within the region, significant migrant expatriates ( mainly in the Gulf states), extreme poverty ( Yemen, Djibouti, Egypt and elsewhere) ,on-going popular protests (Iraq , Algeria, Soudan, Lebanon) civil strife or regional wars ( Syria, Yemen, Libya) , Israeli siege ( Gaza) and Israeli occupation ( Palestinian West Bank), are other facilitating factors for the spread of the disease.

May be the only positive element in this gloomy picture is the age pyramid of the Arab MENA population as the Youth ( 0-25 years) represent almost 50 % of a total population of 430 million Arabs, while the most vulnerable segment of the population ( more than 65 years of age) does not exceed 8 to 10 % in comparison with 22-25 % in Europe. But this is a meagre solace as the combined other factors exact an important human toll and unbearable economic consequences, laying bare States’ mismanagement and inefficiency, the glaring absence of a regional response and the paralysis of the Arab League.

In the Arab Gulf Region, the pandemic struck at the worst moment marked by plummeting oil prices to unprecedented level since 1982, as the economic recession has slowed global demand on oil. However, these countries have better-staffed and equipped health systems and sufficient financial resources to cope with the disease[31]. But expatriate workers in these countries have been disproportionately impacted as businesses and construction projects were brought to a halt. With the depletion of their financial remittances, millions of families in the Arab region and in Asia (Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Philippines, Indonesia etc) are likely to face severe economic stress.

Saudi Arabia, the most populous country of the Gulf Cooperation Council, has been triply battered: first by its self-inflicted oil price war which drastically reduced its oil revenues, gravely impairing its diversification strategy called Vision 2030, and secondly, by the Coronavirus pandemic whose impact has been severely felt in Saudi Arabia itself and in the Moslem World large, as Saudi Arabia quarantined entire cities, imposed curfews that include the Holy Shrines of Mecca and Medina, suspended year-round pilgrimages (UMRAH) and called on Moslems to delay plans for the Hajj (the great pilgrimage)[32]. And thirdly, by the war it spearheaded in Yemen, since 2015, squandering billions of dollars.

The concomitant occurrence of Coronavirus, oil slump, and the war in Yemen put the Saudi Monarchy under stress. It had to struggle against the pandemic and at the same time it had to mitigate its economic impact on Saudi welfare system. That’s why the Saudi Government announced packages of financial rescue measures, in what Yasmin Farouk considered to be “in perfect logic with the rentier-state behaviour[33]”.

Saudi Arabia has weathered many storms in the past. But this time, the context is totally different as the financial resources of the Kingdom are dwindling and its welfare system shrinking[34]. Undoubtedly The social, political and geopolitical impact will be severely felt.

Iran, the Saudi rival, is faring even worse. It became the hotspot of the pandemic, in MENA Region, with thousands of dead. As in the case of Saudi Arabia, the country faces a triple challenge: the pandemic, the oil price collapse and American sanctions. The UN Secretary General, Joe Biden -the presidential candidate-the NY Times editorial board, and many other voices called for lifting, or easing the sanctions on Iran, but these voices have been unheeded by Trump administration. No wonder therefore if Iran’s projected GDP for 2020 may contract by as much as 25%. Yet, the launching of a military satellite during the pandemic perfectly illustrates Iranian self-pride and resilience.

The United Arab Emirates have not been spared by the pandemic, but with sovereign funds exceeding one trillion, the country will weather the economic storm. Nevertheless, the halt of the tourist activity, the probable postponement of Expo 2020 in Dubai (which was expected to attract some 20 million visitors), the grounding of its Air fleet, the slump in the transhipment industry (mainly in Djebel Ali) will be felt very hard. All these sectors will not recover very soon. The same can be said of other Gulf States such as Qatar, Kuwait and Oman, although the situation of Oman is worse as this Sultanate has smaller financial reserves (only $18 billion) and almost no significant foreign investments that can offset the oil price collapse.

The Pandemic is having a devastating impact on Iraq, another oil-exporting country. The chronic political instability of the country and the street protests against the corruption and inefficiency of the political system are aggravating factors that will increase the misfortunes of the country whose GDP may decrease by 10 to 15 %. The depletion of Iraqi financial reserves may tense relations with the Iraqi Kurdish Autonomous Region. While the resurgence of the remnants of the Islamic State (ISIS) is another worrisome nightmare.

The pandemic hit Lebanon while the country was grappling with a crippling financial crisis that led to a 50% devaluation of the Lebanese pound and to debt default (March 2020), and facing huge street protests against the corruption and the incompetence of the political elite. Amazingly, the pandemic did not stop the protests as Lebanon is on brink of collapse.

The pandemic dealt a major blow to Egypt with its 110 million inhabitants. The country is the least prepared to deal with a pandemic of this scale. In the initial phase, the government strived to hide the gravity of the situation, quarantined the information, expelled some foreign journalists and cracked down on activists and critics who accused the authorities of failing to provide health facilities and economic relief. But later, it had to admit that the virus is poised to inflict heavy human toll and economic disaster. Indeed, the tourist industry, which is a main source of revenue ($12.6 in 2019) and employment has been paralyzed. Migrants remittances have dwindled and the Suez Canal transit fees (an average of $ 5.5 billion every year) have diminished drastically as international trade has slumped.

We don’t have sufficient information about the impact of the pandemic in the conflict-ridden countries such as Syria, Yemen and Libya. What it is alarming, in these countries, is that “a major pandemic was not enough to make guns fall silent”. For that reason, the impact will be unbearable. In Yemen, almost 80 % of the population need humanitarian assistance and many wars are being waged simultaneously in the country. What’s more, a UAE backed militia in Southern Yemen set up a “Southern Transitional Council”, and declared “self-rule”, on April 25,2020. adding a “civil war within a civil war”[35] . The declaration of “self-rule” was rejected by the Saudi-led coalition, thus straining relations between Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In Libya, the pandemic did not discourage warring factions to continue fighting and calls for a humanitarian cease-fire remain unheeded. In Syria, where medical equipment is scant, and where many of its hospitals have been destroyed and medical personnel killed or exiled. Coronavirus has been an unwelcome addition to the misfortunes of the country. The regime claims controlling the disease, but what it controlled, in reality, is “the discourse about the disease”[36].

Jordan has also been affected by Covid-19 and it took tough measures to curb its spread, including curfews, and surprisingly enough, Jordan has been successful in containing the disease.

This is not the first time; Palestine is confronted with a health disease. Already in 1838, an outbreak of plague took place in Palestine, with two hotspots in Jerusalem and Jaffa. An American scholar, Edward Robinson, who studied the period, wrote about quarantine and lockdowns to limit movement into and out the two epicentres[37]. But in 2020, the context if different as the population is 20 times bigger and Palestine is either occupied or besieged. Yet, in spite of these adversities, the Palestinian territories, in the West Bank, have coped sufficiently well with the disease. There have been few deaths and most of them in East Jerusalem which is occupied by Israel. The situation in the Gaza Strip is more worrisome as this tiny enclave of 365 km2 is the most over-populated (2 million inhabitants) place in the world after Singapore and Hong-Kong. Already locked down by the Israeli siege, since 2007, the population found itself trapped by the Coronavirus. But Gaza lacks medical equipment, and its hospitals are under-staffed and some have even been destroyed by three Israeli offensives between 2008 and 2014, and there are only 2300 beds for 2 million inhabitants. In a region where families composed of three generations live under the same roof, and where “each individual has an average of 0,18 square meter[38]”, social distancing it almost impossible. To this, one has to add scarcity of drinking water and frequent electricity power cuts. In these conditions, if the spread of the pandemic is not rapidly contained, the consequences might be tragic[39]. Israel allowed the entry of some medical equipment as it came under increasing international pressure, but the population feels doubly trapped by the siege and, now, by the epidemic.

North African countries are also severely hit by Covid-19. They also locked down their population. Algeria seems to have registered more deaths than Morocco, Tunisia or Mauritania, as its health sector, coupled with dysfunctional bureaucracy, suffered from lack of medical equipment and sufficient medical personnel. An aggravating factor may have also been the presence in Algeria of almost one hundred thousand Chinese workers and expatriates with frequent connections with China[40].

The socio-economic consequences in all Maghreb countries will be devastating not only because of the cost inflicted by the pandemic but also because European lockdown will further squeeze their economies. Algeria will be hit harder as the country is severely battered by the steep decline of oil revenues. The only good news for Maghreb leaders is that the Pandemic offered them an opportunity to ban all street protests[41], as each of Central Maghreb countries have sustained political protests calling either for a new political system as in Algeria or for more “accountability” and transparency as in Morocco and Tunisia. Thus, the pandemic offers a respite to the ruling elites of the Maghreb. But if these elites fail in tackling the pandemic and its effects, trust gap between them and their citizens will widen even further.

Finally, Israel has not been sheltered from the pandemic either. The acting Prime Minister, Netanyahu, declared a state of emergency, quarantined the population, mainly in areas inhabited by Orthodox Jews and Haredim, and approved the use of mobile phone geolocation technology to track and trace people who may have been in contact with infected patients. In spite of these measures, the pandemic has not been contained. But Netanyahu reaped a success on the political front as he succeeded in convincing his rival Benny Gantz to form a Unity Government[42], allowing himself to remain as prime minister for the coming 18 months and thus avoiding indictment, prompting this harsh comment of Eran Etzion : “ The Covid-19 will hopefully be beaten but the virus of voter distrust in Israeli-democracy has now infected the entire body public”[43] .

2. The economic cost of Coronavirus on the Arab Economies

All the forecasts by the World Bank, the UNDP, and the Economic Commission for Western Asia predict the biggest devastation of Arab economies in the last 40 years. In the hypothesis that the pandemic does not recede before the end of the year, I estimate the total GDP, in the Arab Countries, to shrink by at least 10 % (in oil producing countries) and by 15% in the other countries. If the sharp decline of oil prices persists for the next six months, more than $ 500 billion will be lost causing rising budget’s deficits that will impair the Gulf region’s quest for diversification. The private sector will feel the bite as it depends directly or indirectly on government contracts and projects. As the public and private sectors, in the Gulf countries, depend on foreign labour, they will be hardly hit as hundreds of thousands of foreign workers and expatriates have left the region. Arab Countries, such as Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Lebanon, will feel the economic pain of oil prices’ slump, as they are doubly affected by the loss in migrants’ remittances and the forced return of their overseas migrants. Kuwait, for example, did not renew the contracts of some 17.000 Egyptian teachers as schools have been shuttered increasing the pressure on the strained labour market in Egypt. If the economic crisis in the Arab Gulf oil-exporting countries continues, they “may revert to nationalising their workforces in sectors where many Arab expatriates’ workers currently occupy mid-management positions”[44]

Capital volatility is another curse. It is estimated that, only between January and mid-March 2020, the region businesses lost $ 240 billion of market capital, 8 % of the region total wealth. Combined with oil prices slump, total debt will increase by 15%, according to the International Monetary fund, i.e.$ 190 billion, to reach $ 1.46 trillion this year.

The Pandemic will ruin the tourism sector in the Arab Countries. This sector plays an oversized role as the region is an open-air museum, awash with cultural heritage, Holy shrines and sandy beaches. It is estimated that Arab countries attract some 100 million tourists and pilgrims every year. Egypt, Morocco, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Bahrein, Tunisia and Jordan are the largest destinations. Tourism contributes 12-14 % of Egyptian GDP, 19% of Tunisian GDP and 15.9 % of Moroccan GDP. The Arab Tourism Organisation estimated total revenues from tourism to amount to $ 130 billion in 2019, which represents 5 % of global Arab GDP. The tourist activity employs almost 15 % of the workforce. Hotels will feel most the squeeze but the food supply chains, farmers, private transport companies will suffer equally. Arab airlines will take a huge hit. The Arab Civil Aviation estimates the loss in revenues for Arab airlines to be around $8 billion until the end of April. Should the pandemic be with us until the end of the year, the loss will exceed $35 to 40 billion. In the Gulf region, where big airlines are a national pride, airlines will be bailed out but, in other countries, airlines may not recover.

The fall-out of the pandemic on total employment in the Arab World will be catastrophic. It is estimated that 1.7 million jobs will be lost, increasing poverty rates to an alarming 30-35 %.

All these scourges are compounded with endemic corruption, political instabilities, control of some economies by the military and elite. As “accountability and transparency are not hallmarks of the regimes”[45], international investors will be wary to invest.

In these gloomy circumstances, there is a glimmer of hope: Moroccan engineers are producing ventilators and Moroccan textile industries are morphing to masks and gowns factories. Similar initiatives could be found in Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia and elsewhere.

3. No change in Regional Dynamics

Will the health crisis serve as an eye-opener and transform the regional strategic dynamics? The question is being widely debated in foreign and Arab media. Sadly enough, the prevailing answer is negative.” The crisis, wrote Dalia Dassa Kaye, is more likely to reinforce and strengthen current negative trend lines”[46]. Rami Khouri is even more blunt:” Arab leaders were already incompetent, then came coronavirus” [47],laying bare their inefficiency. The Arab League remained as a bystander and, as Haizam-Amirah-Fernandez ironically comments:” All it has managed to do is to postpone the Arab Summit scheduled to take place in Algiers, on March 30”[48] , to mark the 75th anniversary of its birth.

The first reactions of incumbent leaders have been disheartening. Some authoritarian regimes cracked down on legitimate speech and stifled the protest movements under the guise of public health safety. Others, mainly in the Gulf Region, engaged in scapegoating. On Twitter, hashtags such as “Coronavirus Qatar” blamed Qatar for the spread of the virus. In Bahrain, the Ministry of Interior accused Iran of spreading the virus which is “an internationally prohibited form of aggression”[49].The Council of Ministers in Saudi Arabia, meeting on March 10,2020, in presence of King Salman, went even further:” Iran bears direct responsibility for the outbreak of corona infection”. Worse, immediately after the outbreak of the disease, Saudi Arabia quickly sent troops to encircle Qatif where Saudi Shia inhabitants are concentrated accusing them of “illegally visiting Iran and bringing back with them the virus” [50].

Against this backdrop, hopes that Covid-19 will serve as a wake-up call have been dashed. Countries are still unwilling to bury the hatchet of recrimination, and war, to heed the needs of their peoples and assuage their fears. Iran and Saudi Arabia are at each other’s throats. But while Iran shows a high degree of incredible resilience, Saudi Arabia’s clout and influence in the Moslem World is dwindling, and its public image has been tarnished. By cancelling the Umrah and the Hajj and banning prayers in the Holy Shrines, billions of dollars have been lost. More importantly, Saudi Arabia used the pilgrimage as “a soft-power instrument…, as 1.8 billion Moslems pray in the direction of Saudi Arabia every day”[51]. But Saudi Arabia wasted this symbolic capital, by politicizing the Hajj, by its meddling in regional disputes (in Libya, Syria etc.), by exporting its Salafist ideology, by cosying up with Israel, by waging the war in Yemen which resulted in humanitarian disaster, by failing the Palestinian struggle for liberation, by campaigning against Qatar , Turkey, Iran and other Moslem states. No wonder if Imams in Libya and Tunisia and many other voices in the Moslem World called for boycotts of al Hajj, which is one of the five pillars of Islam. While other Moslem countries are challenging Saudi Arabia “pan-Islamic leadership”.

Internal strife is still raging in Libya and may even plunge the country in the abyss after Khalifa Haftar, on April 27,2020, claimed he has a “popular mandate” to govern Libya. There is no lull in the war of Yemen. Worse, the declaration of “self-rule” in Southern Yemen by the UAE-backed Yemeni militia and the establishment of a “Southern Transition Council” (STC), on April 25,2020. added a “civil war within a civil war”[52]. The declaration of “self-rule” was rejected by the Saudi-led coalition, thus straining relations between Saudi Arabia and the UAE, both members of the Arab coalition. The STC declaration may lead to a three-way split of Yemen, with Houthis controlling the North (including Sanaa), the new Southern Transition council controlling Southern Yemen including Aden, and the Hadi’s government controlling some dispersed governorates.

Algeria and Morocco are still at loggerheads. Covid-19 has been exploited by the Syrian regime to show that the Syrian regime is efficient in handling the pandemic and by Israel in the pursuit of its settlements’ expansion in Palestinian occupied territories, as international media attention has shifted to the global pandemic.

Some countries, like Iran and Iraq, Egypt, released thousands of prisoners but it was not out of compassion but of necessity, but Israel did not release one single Palestinian prisoner, although the health crisis forced Israel to cooperate with the Palestinian Authority. There has been a brief lull in the battle in the province of Idlib but Turkey clashed with Ha’yat Tahrir al Sham (HTS) in Idlib and with Kurdish militants who seized the opportunity of the virus to harass Turkish patrols in North East Syria. Iraq remains vulnerable to ISIS resurgence and to proxy wars on its soil. It is possible that the economic cost of the pandemic will reduce Iran’s capacity to meddle in regional affairs, mainly in Syria. However, such a probability will not necessarily weaken the Syrian regime as other countries, like the United Arab Emirates, are stepping in Syria, shoring up the regime in a bid to stem Iranian influence. Lebanon suffers from the intertwined interests of Iran, Syria and Hezbollah and the country is on the brink of collapse.

On the whole, the pandemic laid bare the inability of incumbent regimes to curb the spread of the virus and to provide collective response. But what is more distressing is the absence of the League of Arab States. The Arab League took no initiative in coordinating production or distribution of protective equipment, in another proof of its structural deficiencies, thus prompting this harsh comment of Marwan Mu’asher, former Jordanian foreign minister:” The Arab League will continue to be mostly focused on issuing communiqués rather than solving real problems”[53]. A Lebanese writer, Hazem Saghiehis even more blunt:” it would be foolish to expect that any hope could come from this wretched institution”[54]. To the discharge of the League of Arab States, one has to admit that it mirrors the fragmentation, the rifts and the polarisation of its member states, and as Arab proverb says: “the jockey cannot run faster than his horse”. And this saying applies to the EU itself.

Undoubtedly, the epidemic could have offered an opportunity to ease tensions, to bridge political gulfs, to put an end to civil strife, to go beyond narrow regime interests, and to flesh out a regional response. Unfortunately given their short-sightedness and lack of democratic legitimacy, Arab and other regional regimes squandered the opportunity.

With the exception of American proxies in the region, mainly Israel, there is almost unanimous popular outrage against the US whose retreat from the region is often described as “good riddance”. Nevertheless, the pandemic could have been a boon for the US to win back the hearts and minds of MENA peoples by showing compassion, easing sanctions, acting as a moderating force or as an even-handed mediator. Such a hope has also been wiped out, further decreasing faith in US policy. Such a development has two effects: the first is the “increasing ownership by regional states in matters affecting their security”[55], and the second, is the increasing influence of China and Russia in regional affairs.

Summing up

The socio-economic impact of the pandemic on the Mena Region is expected to be devastating, not only because of the inefficiency of State policies, but also because on of the extreme vulnerability of the Arab economies to external determinants[56] such as oil demand, tourism, trade, transport and migrants ‘remittances. Undoubtedly, the economic collapse will further increase unemployment and poverty rates. Geopolitically, the pandemic is not set to have significant impact on MENA countries. Authoritarian regimes will remain intact and “no one should expect these regimes to proactively embrace genuine reform under any circumstances”[57] Some conflicts may be frozen but as the pandemic recedes, they may be re-activated. The remnants of the Islamic State claim that the Covid-19 is “God’s retribution” against its enemies and are re-surfacing in Syria and Iraq. Iran’s influence in the region may be curtailed. Gulf States will not shelve their differences any soon. Turkey may temporarily refocus its attention on the domestic front but meddling in Syria and Libya will not stop. Israel will further tighten its grip on the Occupied Palestinian territories in spite of international condemnation. Algeria and Morocco will continue their squabble. The Libyan crisis will deepen further after Khalifa Haftar claimed he has a “popular mandate” to govern Libya (27 April 2020). Increased difficulties and strains for refugees and displaced people may create incentives for radicalisation. To put is in a nutshell: Before the pandemic, Arab outlook was gloomy. With the pandemic, Arab general outlook is likely to be gloomier.

PART IV:

The European Union and MENA countries in time of Coronavirus

The pandemic will be recoded in History books as the challenge of our lifetime. But will it be a “game-changer” in the relations between the European Union and its “nearest abroad”: the Mediterranean and the Arab World?

If we assess EU policies towards the Mediterranean and Arab region in the last decade, as I did in my last books and articles[58], It is hard to believe that the Pandemic will be a “game-changer”. Yet, the EU cannot simply watch the unfolding consequences of the pandemic without reaction. In the past decade, it reacted to the Arab Spring that began in late 2010, to the military coup in Egypt (2013) to the proclamation of the Caliphate of the Islamic State (2014),to the war in Eastern Ukraine and to the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, to the Iran’s nuclear issue in 2015, and to the war wages in Yemen by a coalition spearheaded by Saudi Arabia (2015). In the same year, it had to grapple with the migration issue (2015), convened the Valetta Summit on Migration (2015), and was confronted with a wave of terrorist attacks in many EU countries. In 2016, the EU reached a 6 billion euros deal with Turkey to prevent illegal crossing to Greece, and in the same year, the EU went through an unprecedented crisis with the Brexit referendum which mobilized the official and media attention. Since 2017, the EU agenda was awash with reactions to the erratic and “disruptive policies of the Administration of U.S President, Donald Trump[59]”, regarding NATO, Brexit, Syria, Iran, China and above all the Arab-Israeli conflict. among many other issues. The withdrawal of the US from the Nuclear Deal with Iran constituted a negative setback in one area where EU foreign policy has achieved a remarkable success.

From 2010 until 2020, Euro-Mediterranean and Euro-Arab relations were put on the back-burner: Financial aid was disbursed but there has been no significant innovative initiative. The questions of democracy promotion, regional cooperation, and security arrangements were eclipsed by more urgent challenges as migration, terrorism, and internal security. The first EU-League of Arab States summit that took place in Sharm-El-Sheikh, in February 2019, was organized in haste and yielded no results.

Will the pandemic put Euro-Mediterranean and Euro-Arab relations on the front-burner and offer a chance for change?

Josep Borrell , the High Representative for Foreign Policy of the EU, gives his answer : “ I think that even we are badly affected by the Coronavirus crisis , we have to show solidarity with other countries who are in a much worse situation”[60].Indeed, in April 2020, the Commission launched “ TEAM EUROPE” to support partner countries fighting against the pandemic. The approach is to “combine resources from the EU, member States and financial institutions, such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)”. The goal is to propose a package of 20 billion euros to help the most vulnerable countries in Africa, Middle east and other regions of the world, and mainly the people most at risk, including children, women, the elderly and disabled, as well as migrants, refugees and displaced persons. The Commission and the EIB have already pledged 15 billion. But as Borrell himself admits:” This is not fresh money…we have to restructure and reorient our resources to give priority to the fight against Coronavirus”. No matter whether it is new money or not, the initiative is laudable. Already the EU offered Morocco 450 million euros, Tunisia 250. Jordan and Lebanon are to receive 240. Smaller sums are promised to other Mediterranean and Arab countries in need. The support of the EU will focus on:

-Responding to the immediate health crisis;

-Strengthening health, water and sanitation systems;

-Mitigating the immediate social and economic consequences.

By marshalling the financial package, the EU seeks as Josep Borell explained: “to defy the critics and demonstrate, in very concrete terms, that it (the EU) is effective , responsible in times of crisis”[61].But for the EU external action to be really effective, it should focus on immediate and long-term challenges.

1.Immediate challenges in the midst of the pandemic

-Refugees should be a first priority of EU action. The rapid spread of the virus in these over-crowded camps in Greece will be difficult to curb as lockdown is almost impossible, and as the refugees live in squalid conditions without running water, let alone soap or protective equipment. Leaving Greece alone in managing the situation, is not an option. EU request to relocate refugees most at risk is not an option either as Greece is at pains dealing with its own health problems. Undoubtedly the cramped camps of refugees in Greece constitute a time-bomb.

But not all is grim: Coronavirus had some positive side-effects related to refugees. Portugal decided to legalise all of its undocumented refugees. Spain, Belgium and Netherlands and other countries suspended deportation of refugees to their countries of origin. Spain emptied its “Centros de internamiento de extranjeros” (CIE). Germany offered asylum to some 50 teenagers. Italy legalized some 200.000 refugees and migrants probably due to shortage of labour force in the agricultural sector, but suspended, on March 12, all hearings and appeals relevant to asylum. All these developments are welcome but the question of cramped hotspots in Greece and Italy and elsewhere will remain daunting challenges for the EU.

The EU should pay special attention to refugees and displaced people in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. It is true that the EU has been generous with these host countries. But displaced Syrians, in Syria itself-mainly in Idlib province- are in dire need of humanitarian and medical help, as most of the medical infrastructure has been destroyed. These refugees may find themselves totally unprotected should Coronavirus break out in their camps.

Irregular migration has to be managed with humanity. As paradoxical as it may seem, the pandemic did not stem the flow of migrants seeking to cross the Mediterranean. Dinghies transporting migrants have been located, and, at least, in one case, Malta called up the Libyan coastguard which took back the 46 people on board, although the rubber dinghy was in European rescue zone[62]. Two other regrettable developments have been reported by Patrick Kingsley[63] : one is related to Maltese army sabotaging a migrant boat off the coast of Malta[64] and the other related to “privatized pushbacks”, in reference to commercial merchant ships returning migrants to war-torn Libya. The UE should not let such abuses to happen.

–Gaza should be another priority of EU action. And indeed, it has been. Immediately after the first two imported cases were confirmed, the Head of EU Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM, set up in 2005) decided to reallocate existing funds, at short notice, to donate a portable thermal imaging fever system to the Palestinian General Administration for Borders and Crossings.

2.EU Mediterranean and Arab Policy after the pandemic

As EU is grappling with unprecedented health and economic crisis, it may not want to raise its profile in MENA region now. But the combination of chronic instability, bad governance and, now the sting of the pandemic and its aftermath directly affect the EU. In the past, as a group of experts of the European Council for foreign affairs warned: the EU has focused on “short-term transactional policies designed to address immediate challenges such as terrorism and migration”[65]. But on the issues of war and peace in the region, the EU has been “off the map”, or simply “irrelevant”, accentuating indirectly the increasing influence of other international actors as Russia, China and even India.

Given the vital interests the EU has in the region, there is an urgent need to critically assess and overhaul all its previous policies, and chart a new course of action. Otherwise” its Ring of friends” may morph into a “ring of fire”. The EU has to consider its long-term interests in the MENA region[66] and not remain obsessed with short-term challenges as migration or terrorism. Coronavirus and its devastating effects on the EU and its neighbourhood should serve therefore as a “wake-up call”.

In the Middle East, the EU disunity , inactions or inconsistencies on major issues , such as Iran, Syria, the Gulf internal disputes, the war in Yemen, the Arab -Israeli conflict, the EU played second fiddle to the US , failed to articulate a coherent, independent and pro-active foreign policy, or simply remained as a bystander.

The EU must salvage the Iran Nuclear Deal (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action), a major achievement of EU foreign policy. It should not allow American sanctions to hurt its own economic and geopolitical interests. Coronavirus has been an opportunity for the EU to showcase its compassionate face. First the EU offered 20 million Euros to the World Health Organisation to fund deliveries of health equipment to Iran. And second, France, Germany and the United Kingdom used, for the first time, Intex , a trading mechanism bypassing US sanctions and allowing them to export medical goods to Iran. These actions go in the right direction. but EU should go further by lifting the sanctions on Iran as they inflict more suffering on the Iranian people, harm EU economic interests without achieving any political gain[67].

As the US may be retreating from the Gulf , the EU should step in with three major tasks : actively mediate to end the internal Gulf rift, convince the Houthi rebels and the Arab-backed Yemeni government that there is no military solution to the Yemen internal crisis and finally to inject new life in EU-Gulf Cooperation Council relations. Keeping aloof or simply expressing “hopes” or “regrets” may weaken further EU’s capacity to make a diplomatic impact in the region.

On the Arab-Israeli conflict, the time of empty declarations, “toothless diplomacy[68]”, words of condemnation and regret, should be over. To be credible, European Foreign Policy should adopt a tougher stance, stick to the UN resolutions, apply pressure and sanctions when necessary. Asking Israel to abide by international law has been a waste of time, as Israel, systematically turned a deaf ear to EU warnings. Labelling Israeli products is worthless: anything produced in any Israeli settlement whether on the Golan Heights or in the West Bank should simply be banned. The EU cannot impose sanctions on Hamas in Gaza and cosy up with Israel. Such an un-balanced position damages EU moral standing. The EU should call on Israel to lift the blockade and to allow unhindered international assistance to the endangered population of Gaza. The EU should also back intra-Palestinian reconciliation talks. The task may seem daunting but this is the only way to make Gaza a “a habitable place”, to regain trust in Palestine and in the region at large and to make Europe a credible actor.

The collapse of Lebanon may trigger civil war or even a regional war. The EU should, in coordination with the international community, save Lebanon. It is true that most of the problems of Lebanon are of its own making, but it is also true that the country has been severely affected by proxy wars on its soil, by the flux of refugees, and by the destabilization of the region as a whole.

The EU action in Syria has been almost invisible. Russia has dominated the scene. The US is withdrawing. Turkey is asserting itself and Iran is meddling in Syrian affairs. The EU provided assistance to NGO’s in Syria and to refugee camps. It helped organise what was called “the friends of Syria”. But the EU has not been a visible pro-active player in Syria. The US withdrawal offers the EU an opportunity to step in and prepare for the reconstruction of Syria.

Some EU countries (France and Spain) are withdrawing their military forces from Iraq. This precipitous move may allow ISIS to resurge. And there is doubt that Iraq has sufficient air and land surveillance to kill in the nib ISIS resurgence. The EU should be prepared to offer its military assistance whether alone or in coordination with NATO. This is not meddling in Iraqi affairs, it is simply extending a helping hand

The EU cannot afford to fail Middle Eastern countries. Vested interests are at stake. With US influence waning in Middle East, the EU has an incredible chance to raise its profile and play a prominent role. If it shies away, then its pretence to play a geopolitical role may become an exercise in fantasy.

Maghreb Countries are EU’s nearest “abroad”, where it has stronger influence by virtue of history, geography, geopolitics and trade. The pandemic and its aftershock will have devastating consequences on Maghreb countries. First, European lockdown will provoke economic squeeze in the Maghreb, as the EU is its main trading partner (65% of total Maghreb trade is done with the EU). Second, migrant remittances will dry up, as Maghreb migrants in Europe will be severely exposed to unemployment. Third, the tourism sector is set to be ravaged as borders are closed and air fleet grounded. Fourth, investors will shy away from the region as they will be looking inward. We should therefore expect a collapse of GDP in all Maghreb countries and a further spike in unemployment and poverty rates.

It would be unwise to think that the mere injection of some “fresh money” in these battered economies would save these countries from collapse or bankruptcy. The EU should go beyond “money”, revamp its short-sighted policies and take steps for lasting regional stability, sustainable economic reform, and promotion of regional integration.

Regional stability requires a more decisive, coordinated and coherent action in worn-torn Libya. The country is enmeshed in civil war between the UN-recognized government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli and the leader of the self-proclaimed eastern-based Libyan National Army (LNA). The war is raging since some years but it took a dramatic turn when Haftar’s army, with some military and diplomatic backing from Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Russia and even France, attempted, in April 2019, to capture Tripoli. Neither side has achieved decisive strategic victory, as Turkey stepped its support to the government of Tripoli.

Libya poses an immediate security challenge to the EU: With more than one thousand kilometres of Mediterranean shores, Libya is the launching pad of irregular migration through the Central Mediterranean Route. Some European countries (mainly Italy and France) are backing rival sides, as the untapped oil potential of Libya excites the appetite of ENI and Total. Others, like Germany are striving to mend the fences between the contending forces (Berlin Conference, January 2020), a mission which should have been undertaken by the EU itself. Moreover, as Libya draws in regional and non-regional backers, the internal strife may lead to a regional conflict. For all these reasons, the EU is concerned that the civil war could degenerate in wider conflict, putting some European countries at loggerheads, worsening regional stability, and swelling the flow of migrants.

In the last years, the EU outsourced the migration issue and financed detention centres in Libya, in what was called as the externalisation of the migration policy. More recently, on March 31, the EU launched the codenamed “IRINI” operation. Officially, this naval mission is designed to enforce UN Security Council Arms embargo in place since 2011. “In principle, the mission sounds good», comments Tarek Megerisi, but “the vast majority of weapons deliveries to Libya do not come from sea. They are either flown in at the behest of the United Arab Emirates or driven across Libya’s land border with Egypt”[69].

Whether IRINI mission will achieve its objective remains to be seen. What is sure however, is that this mission in the Eastern Mediterranean will be seen as a move intimately linked to the Turkish-Libyan territorial agreement in East Mediterranean, and to the Turkish backing of the Government of Tripoli. Indirectly it weakens the UN-recognized government of Tripoli, something which puts the EU at odds with its own proclaimed policy of not taking sides in the conflict. That’s why, the April 25, Joint call for humanitarian truce in Libya, made by the Foreign ministers of France, Italy, Germany and Josep Borrell, the EU Top Diplomat, will sound hallow in Libyan ears. Indeed, few days later, Haftar proclaimed himself as the “ruler of Libya”, leaving everybody flappergasted.

If we consider that the Libyan issue should be a priority for EU foreign policy, it is not only because of the risks related to migration or proxy wars, it is also because Libya’s destabilisation poses serious risk to the security and stability of neighbouring Maghreb countries. Undoubtedly, much of Tunisia’s ills are intimately linked to the Libyan crisis, with which it has 459 kilometres borderline and which was one of its major exporting markets. Algeria is less dependent on the Libyan market, but it has 982 kilometres long border with it. Therefore, any destabilisation of Libya will necessarily spill over Algeria, in many ways. Morocco will not be immune neither as the crisis of Libya reverberates on all Maghreb countries.

But Libya is not the only wound of the Maghreb. Algeria and Morocco are still turning their backs to each other, with borders closed since 1994. And there are still bickering on the question of the Sahara, putting the Arab Union of the Maghreb-the Maghreb Regional initiative- at risk of total paralysis.

3. Regionalised Interdependence

Against this backdrop, the action of the EU should concentrate on facilitating a political solution for the Libyan crisis, reconciling Maghreb Countries, and pushing for regional integration, and promoting what I may call “Regionalized interdependence”.

As the pandemic revealed EU dependence on supply chains from China for medical equipment and medicines, and its vulnerability to blackmail and disruptive measures, it is ripe time to think about the relocation of some industries (mainly related to the Health sector) in the Maghreb and in the Mediterranean regions. Such a policy has many advantages. First, the Maghreb and other Arab countries are the immediate neighbours, their youth is educated, labour cost low, and there is a demand for employment. The redeployment of industries in the Southern Region, reduces the cost of transport, creates jobs and prosperity and increases the interaction between the EU and its neighbours. The more developed is the Arab region, the better off is Europe. Investing in development in its immediate neighbourhood, has many advantages for the EU. First, it diminishes the “push factor” to migrate. Second, it translates in increasing trade between the two regions. Third, it stems the wave of discontent. And fourth, it helps the growth of middle class and the emergence of a local industrial elite, indispensable factors for the consolidation of democratic systems.

This is a more rational course of action.EU should draw lessons from Coronavirus crisis : Investing in China creates jobs in China and makes China more prosperous, and more assertive , but , at the same time, it contributes to the de-industrialisation of Europe and makes it weaker, dependent and vulnerable to disruption of supply chains. While a real co-development strategy with its Mediterranean and Arab neighbours creates prosperity and stability for them and prosperity and security for Europe.

Conclusion

No doubt that Coronavirus is a life-shattering event and a defining

moment. Its effects will be felt for years. This unprecedented health crisis

can be a bane or a

boon. A bane, if Europe goes

back to “business-as-usual”, or a boon if it transforms this pandemic into a

new opportunity through a substantial overhaul of its political and economic

policies at home and in its immediate neighbourhood. Regionalised interdependence as

suggested in this paper, should become the backbone of a revigorated EU-MENA

relations.